Exhibit A: The learned Miss Jones, one of the two kittens we adopted for Christmas. Her brother is a cat-man of more plebeian tastes and prefers to spend his time rolling around under the sports section of the newspaper.

Exhibit B (located beneath Exhibit A): A sampling of the books I’ve read so far in my summer of research. I’ve only skimmed to the good bits in the chronicles at this point, but I’ll be going back for close reading later (and probably more than once).

The weather has been conducive to long uninterrupted spells of reading in the garden, so I’ve also managed to plough through quite a bit of other material, amongst which:

- Michael Bennett’s Richard II and the Revolution of 1399 (which is still irritating me with its referencing, or lack thereof, but this post by Gesta on writing book reviews makes me realise I was probably unfair in blaming Bennett instead of his publisher.)

- Nigel Saul’s Richard II and his EHR article “Richard II and the vocabulary of kingship”. I was surprised to find Saul’s 1997 book is the first scholarly bio of Richard II since Anthony Steel’s 1962 outing.

- Lynn Staley’s Languages of Power in the Age of Richard II. I found this a richly detailed interdisciplinary study of the social and political contexts of works by Chaucer, Gower, the Gawain poet and other 14thC texts. It also offers some valuable insights that I haven't come across elsewhere (yet) into Charles V of France's influence on Richard II's court and the connections between literary patronage and ideas about kingship.

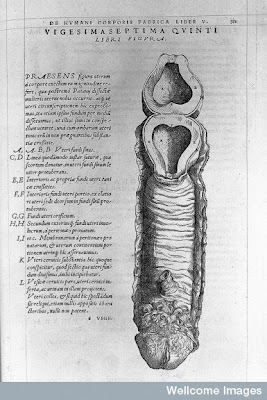

- Jeffrey J. Cohen and Bonnie Wheeler’s Becoming Male in the Middle Ages

- Paul Strohm’s Hochon’s Arrow: The Social Imagination of Fourteenth-Century Texts

- Carolyn Dinshaw’s Getting Medieval

- Karma Lochrie et al., Constructing Medieval Sexuality. I read Mark Jordan’s chapter, “Homosexuality, luxuria and textual abuse”, on the bus. That got me some odd looks.

- Assorted articles on feminist and queer theory

Over the last few weeks, I’ve also developed a much more refined picture in my mind of the approach I want to take to this research project and of the specific questions I’m going to be working to answer. Thanks to some unexpected connections the background reading has been sparking, my ideas have changed a fair amount since their initial incarnation. I expect they’ll morph quite a bit more in the coming months but at least now I feel like I have a clear direction and some markers to follow. (This is just as well, because it won’t be long before I need to front up to the Postgraduate Research Committee with the formal research proposal.)

I’ve been relieved to find that, as I suspected, I’m going to be covering some solid new ground and my advisor is pretty excited about it. I went through these weird phases of anxiety at first, swinging between ‘wow, I can’t believe no one has thought about this topic in this way before,’ and ‘crap, maybe no one has done this before for a good reason’. Now that my project has been approved in principle by both my advisor and the postgrad research co-ordinator (thus validating it is indeed worth pursuing), I’ve settled into a sort of steady state where I crack open each new book or article alternately hoping to find something along my lines that will be useful, and fearing that I’ll find my great original idea isn’t so original after all.

Here’s a question for all you scholarly and creative types, though. I’m really excited about this project and want to prattle on about it to anyone who will listen. But at the same time, I’m instinctively wary about putting too much detail about it on the public interwebs, given those cases we all hear about of academic plagiarism and people having their ideas nicked before they can take credit for them. In fact, I haven’t mentioned a couple of the books/articles I’ve read, as I feel like the titles alone could give away a bit too much about the way I’m thinking (this is, of course, assuming anyone but me even gives a damn). Is this just paranoia? Am I being overly cautious? Do you talk about your original ideas and research in any specificity online before you present or publish in a more formal context? If so, have you ever had an ‘oh crap’ moment, where you suspect someone else has pinched your work?